See Below for Full Presentation

Sarah T. Barnes

North Carolina State University

Com 523 - International and Intercultural Communication

Melissa Johnson

23 November 2020

Introduction

In the year 2020, the Coronavirus pandemic disrupted many aspects of life globally, especially how users interacted with social media (Koeze & Popper, 2020). As cities and states shut down across the United States and around the world, there was a shift in both consumers’ needs and advertiser’s avenues for marketing. With more potential customers stuck at home - observing stay-at-home orders, quarantining, or working remotely - there was an increase in activity on social media platforms to fill the time that would usually be spent socializing with friends in person (Koeze & Popper, 2020). With consumers being stuck at home and stores unable to sell products in person, online advertising and e-commerce skyrocketed globally. Social media marketers and influencer marketers took advantage of their target audience spending extra time on their phones and pushed their brand’s online presence.

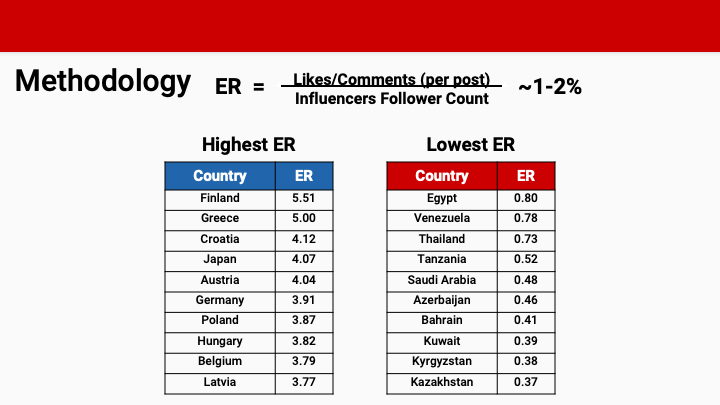

During the age of social media, marketing and advertising departments have taken advantage of e-commerce, utilizing “popular” social media influencers to increase their brand’s visibility. Platforms such as Instagram and YouTube allow brands to sponsor influencers who then talk about their product or brand. According to Tafesse and Wood, influencer marketing is an effective way for brands to communicate with their customers via social media (2020). Brands will sponsor celebrities and influencers to promote their products to the influencer’s following, often upwards of several million social media users. While these influencers often have millions of followers, the most important statistic is influencer engagement, or how often followers interact with the influencer’s posts (Niciporuc, 2014). This “Engagement Rating” (ER) can be calculated by combining the influencers likes and comments (per post) and dividing it by the influencer’s follower count (Guttmann, 2020).

Different demographics interact with social media differently. Country of origin, age, and gender can all affect how someone engages with social media platforms and posts. The ER for individual countries can vary greatly based on factors such as average age of population, access to technology, and political structure. Knowing that different countries tend to engage with Instagram posts at different rates, it is beneficial for influencer marketers to understand the nuances of their target countries. By breaking down the ER based on a country’s culture, marketers can better tailor their influencer selection and marketing strategy in order to get optimal engagement on their sponsored posts.

This paper aims to understand how varying cultural dimensions of a country, as described by Hofstede, can impact the success of influencer posts around the globe (2011). By first identifying the countries with the highest and lowest engagement ratings on Instagram, this paper seeks to identify which cultural factors, if any, likely influence an increase or decrease in Instagram engagement rating. This could allow influencer marketers to better understand where their sponsored product posts will receive the most engagement. If these cultures’ engagement rates do indeed correlate with Hofstede’s dimensions of culture, then influencer marketers may be able to target specific audiences via influencer’s posts and positively predict engagement on each post for each country, which will save those brand’s money as well as increase revenue from those countries.

Literature Review

The analysis of social media engagement has been a crucial tool for social media influencers and marketers to understand their audience and their reach. While there have been studies to uncover social media engagement across influencers and countries, there has been little research on why certain countries and cultures interact with social media in different ways. Due to the nature of social media, it is important for advertisers to understand why an entire culture may be inclined to with an Instagram influencer’s posts. This could then be taken one step further to provide insight into what social media tactics are likely to affect an individual of that culture.

Social Media - Influencers and Engagement

Social media has taken over the way we socialize in the 21st century. There are several popular social media platforms in use today around the world, including the global leader, Facebook, as well as YouTube, Instagram, Twitter, WhatsApp, Pinterest, and Snapchat, among others (Bullock, Wright, & Gurd, 2020). These media outlets have become fantastic avenues for companies to advertise their products or services to specific target audiences. A large portion of this interaction is done via influencer marketing. Influencer marketing is a strategy where brands team up with influencers to reach the influencers’ audience through sponsored posts (Tafesse & Wood, 2020, Argyris, Wang, Kim, & Yin, 2020). Sponsored posts are when a brand will pay an influencer to post about their brand, product, or entire product line. A social media influencer is defined as a non-celebrity who has gained followers on social media by posting photos, videos, or blurbs (such as Tweets), and by interacting with their followers (Argyris, Wang, Kim, & Yin, 2020). Influencers with large followings, which includes many celebrities, will strategically team up with brands and receive sponsorships based on their audience and following.

A metric influencer marketers must pay attention to is the influencers’ engagement rating, not just their follower count. Countries with high engagement ratings have social media users that interact more frequently with these sponsored posts (Guttmann, 2020). Similarly, countries with the lowest engagement ratings will likely have their posts interacted with the least (Guttmann, 2020). Due to this, the engagement rating is a prime measure of a country’s receptibility to advertising and marketing strategies.

Cultural Dimensions

Geert Hofstede outlined six cultural dimensions: Power Distance, Individualism, Masculinity, Uncertainty Avoidance, Long-Term Orientation, and Indulgence (Hofstede, 2011). Those dimensions are described in more detail below.

Power Distance (PDI) is “extent to which the less powerful members of organizations and institutions (like the family) accept and expect that power is distributed unequally.” (Hofstede, 2011). PDI can be considered Large or Small, Larger PDI is closer to 100, while Smaller PDI is closer to zero.

Individualism (IDV) is “the degree to which people in a society are integrated into groups” and is opposed to Collectivism (Hofstede, 2011). More individualistic countries fall closer to 100, while more collectivist countries fall closer to zero.

Masculinity (MAS) is “the distribution of values between the genders which is another fundamental issue for any society, to which a range of solutions can be found” and is opposed to Femininity (Hofstede, 2011). More masculine countries are closer to 100, while more feminine countries are closer to zero.

Uncertainty Avoidance (UAI) “deals with a society’s tolerance for ambiguity” and should not be confused with risk avoidance (Hofstede, 2011). Strong uncertainty avoidance is closer to 100, while weak uncertainty avoidance, also known as uncertainty tolerance, is closer to zero.

Long-Term Orientation (LTO) “deals with change” and how that culture prepares for the future (Hofstede, 2011). Longer-term orientation, also known as “flexhumility”, falls closer to zero, while short-term orientation, also known as monumentalism, falls closer to 100.

Indulgence (IND) deals with the “gratification versus control of basic human desires related to enjoying life (Hofstede, 2011). The most indulgent countries fall closer to 100, while the most restrained cultures fall close to zero.

There are numerous studies revealing limitations of Hofstede’s model in current research, such as the different meanings of each dimension across cultures. Additionally, several studies only focus on one or few countries. For instance, there is one discussing Hofstede’s dimensions of culture in international marketing studies (Soares, Farhangmehr, & Shoham, 2006) and another focusing on Hofstede’s cultural dimension’s effect on Ghanaian marketing culture (Ansah, 2015).

To further examine the potential gaps in information identified by the previously mentioned studies, one can look at an article by Gravili in which the author discusses the relationship between culture, knowledge sharing, and social media use. This study looked at different countries and compared various cultural dimensions, outlined by Hofstede, and social media penetration data based on Social, Digital & Mobile Worldwide Reports in WeARESocial’s series (Kemp, 2014). This study examined the social media penetration of 60 countries based on active users of the largest active social networks in each country (Gravili, 2016). Gravili states that because traditional feminine countries tend to have good relationships with peers, supervisors, and subordinates, the results demonstrate that these countries have “developed an elevate[d] social media penetration” (2014). While Gravili studied the knowledge sharing process for each country based on that country’s most popular social media platform, this study focuses on social media engagement on Instagram.

Methodology

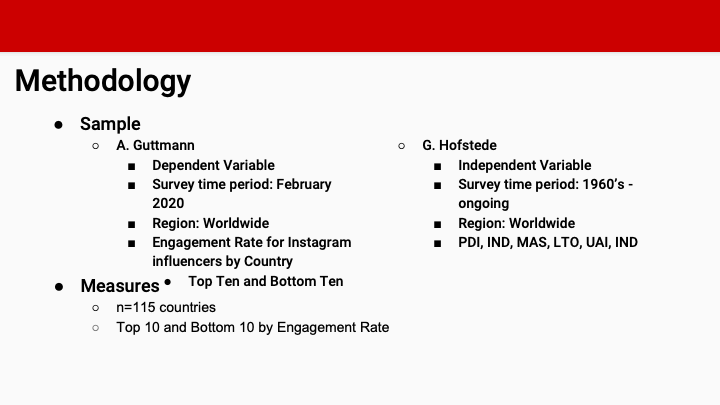

In order to examine the possible correlation between individual countries’ Instagram engagement rating and Hofstede’s six dimensions of culture, this study utilized secondary quantitative data from A. Guttmann and G. Hofstede. Guttmann provided data on the top ten countries and bottom ten countries based on their Instagram ER percentage and this study made note of their scores in Hofstede’s dimensions. The goal of evaluating both sets of data together was to establish a correlation between a country's score in at least one of Hofstede’s six cultural dimensions and their Instagram ER. The results could help influencer marketers better market their promoted posts toward specific audiences in countries based on those country’s cultural dimensions.

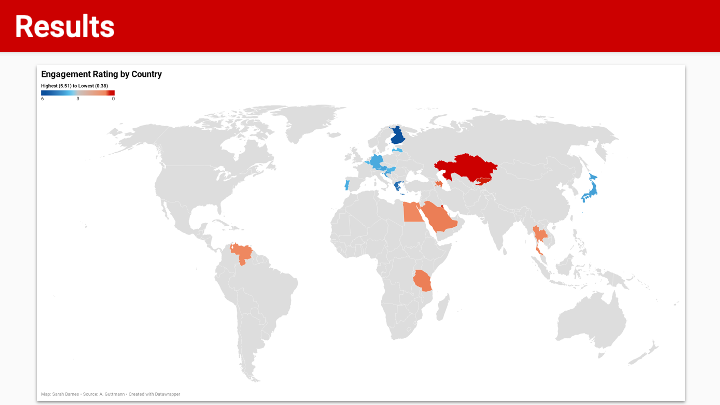

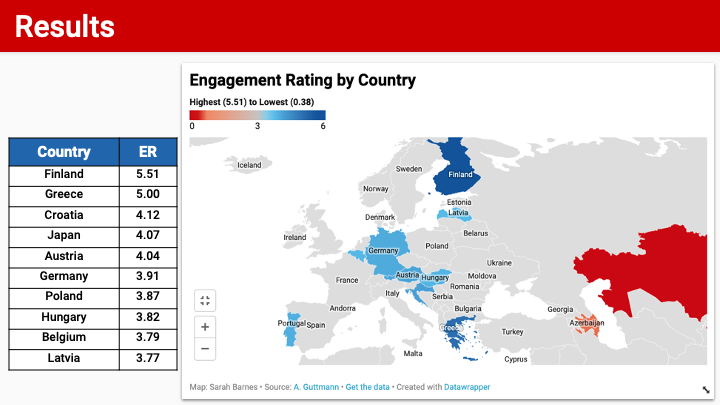

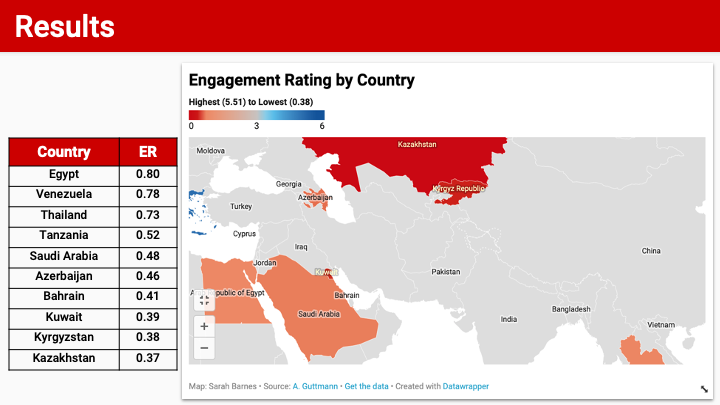

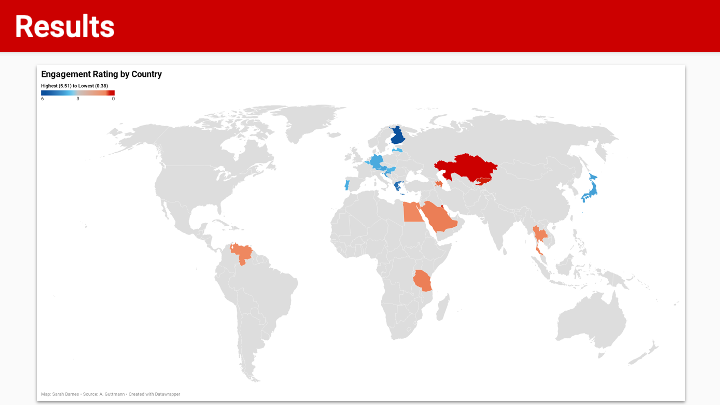

Dependent Variable - Social Media Engagement

Given that social media is a rapidly changing entity, it was important to use the most recent data available, so A. Guttmann’s data was selected because it was collected in February 2020. The data gathered by Guttmann outlines the ten countries with the best ER (see Table 1) and ten countries with the worst ER (see Table 2). The two groups, labeled “Top Ten” and “Bottom Ten” are shown below and ranked according to their Instagram ER, with Finland having the best engagement and Kazakhstan having the worst engagement:

Independent Variable - Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions data has been compiled over the last 60 years. Based on the most recent data collected in 2014, this study used the two groups outlined above by Guttmann to pull out the twenty countries’ scores in each of these six dimensions. The sample size based on Guttmann’s data was twenty countries, however these countries were analyzed against the average of 115 countries with data for each of the six dimensions (See Tables 3 and 4). Additionally, it is important to note that three countries in the bottom ten group have no cultural dimension data available (Table 4).

This research proposes a simple model for statistical testing: is there any positive or negative correlation to prove and help predict a country’s Instagram engagement rating? The underlying assumption from this is to understand if Instagram engagement rating is correlated or not with Hofstede’s cultural dimensions.

We hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 1 - Hofstede’s cultural dimensions influence Instagram engagement rating.

Hypothesis 2 - The relationship between Instagram engagement rating and Hofstede’s cultural dimensions is positive/negative and relevant.

Findings

For this study, the main insight that will be explored is where the average cultural dimension scores of the top ten and bottom ten countries stand compared to the average of all 115 countries. The following tables expand on the information from Tables 3 and 4, with the addition of averages from the top ten (Table 5) and bottom ten (Table 6) countries to attempt to provide support for the hypotheses.

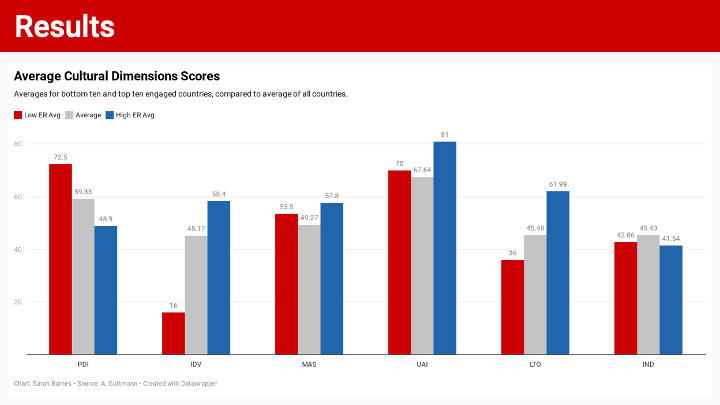

There are several conclusions we can draw from these results. To see if either of the hypotheses were supported, these results will focus on the difference in averages for power distance, individualism, and long-term orientation.

Power Distance

Looking at Table 6, the low engagement rating group of countries had a higher power distance average, with a PDI of 72.5, compared to the high engagement rating group (Table 5), with a PDI of 48.9. This compares to the average of all 115 countries, with a PDI of 59.33. This supports the hypothesis that ER and PDI have a negative correlation. This could provide evidence that since the low engagement rating countries see their power distance as a basic fact of their society, they don’t have the societal freedom that could lead to higher engagement. Additionally, the lower PDI for the high engagement rating countries could mean that those countries' cultures believe their power distance is more equal and because of how that affects their society, those cultures feel more free to engage with content.

Individualism

Comparing the individualism scores for the top ten and bottom ten countries, we can see that they are drastically different from the average of all 115 countries. The low engagement rating IND average score is 16 (Table 6), while the high engagement rating IND score is 58.4 (Table 5), compared to the average of all 115 countries which is 45.17. This supports the hypothesis that ER and IND have a positive correlation. This result was unexpected based on previous research that predicts that countries who are more collectivist will tend to engage more with their peers to create a sense of belonging and support the “we” rather than the “I.”

These results could provide evidence that more collectivist countries do not engage with Instagram posts as often as individualistic countries. This could be a product of those individualistic countries being selfishly focused on boosting their own Instagram posts and so they may be more likely to engage with other posts in order to come across as a team player when they are actually doing so for their own selfish gain.

Also, it is important to note that this could be a result of the IDV only having cultural dimension scores for two countries, Venezuela and Thailand. This data, as well as data for PDI, MAS, and UAI could be skewed toward the scores for those two countries and are not representative of all ten countries with the lowest engagement rating.

Long-Term Orientation

Finally, looking at the long-term orientation averages, we can see that the low engagement rating LTO average of 36 (Table 6) is below the average of all 115 countries with an LTO average of 45.48. This data suggests that countries with a low engagement rating are less focused on the future, tend to adapt to their circumstances and attribute their success to effort rather than luck. Counter to the low engagement group, the high engagement rating group averaged higher than the average of all 115 countries, with the LTO of the high engagement group at 61.99 (Table 5). This supports the hypothesis that LTO has a positive correlation with a country’s ER. This could indicate that the higher engagement countries are engaging with Instagram posts more because they are living more in the moment, whereas the lower engagement countries do not consider engaging with Instagram posts a high priority for their future success.

Discussion

There are several limitations of this study. Mainly, the data collected for the low engagement countries from Hofstede’s cultural dimensions is incomplete. This could lead to the data being skewed because the average dimension scores are only taken from two countries or seven countries, which is not a large sample size.

Also, there could be additional external factors that affect the country's ER, including but not limited to: political climate, Internet penetration, mobile phone penetration, and demographic breakdown. Future studies could include these metrics to draw more sound conclusions regarding the relationship between ER and cultural dimensions.

Another limitation is that the two datasets used come from two different time periods. While countries do not go through a drastic cultural change, it would have been more accurate if the data came from the same time period. Guttmann’s data was collected in February 2020, while Hofstede’s data was from several different time periods. However, Hofstede states that the data he has collected has not changed considerably over time, so this limitation should not affect the findings of this study considerably.

Future research could expand beyond just engagement rating data from Instagram to exploring other popular social media platforms, such as Facebook. Looking at several social media platforms at once, or potentially focusing on the most popular social media platform for individual countries, could provide additional useful metrics to influencer marketers who want to maximize their time and money spent on these campaigns.

For future studies, the addition of a qualitative component could enhance these findings. Including qualitative interviews of country’s citizens who use social media about why they interact with Instagram the way they do, could lead to different conclusions about their cultural preferences and go beyond correlation to establish causation.

Conclusion

With more and more consumers around the world shifting toward e-commerce, it is important for influencer marketers to know how to best utilize the platform and the influencers in order to optimize their return. With this study supporting the hypothesis that there are correlations between a country’s ER and their power distance, individualism, and long-term orientation, marketers can observe a country’s cultural dimension score to predict how a sponsored post will perform in that country’s culture. This study, compounded with future research, can aid influencer marketers in the process of selecting an influencer to sponsor. Based on knowledge of each influencer’s audience’s cultural dimensions, the sponsored posts could be catered to achieve the specific goal of the advertising campaign and attempt to maximize their sponsorships to the influencer’s audience’s culture.

References